NIST Develops New Testing System for Carbon Capture

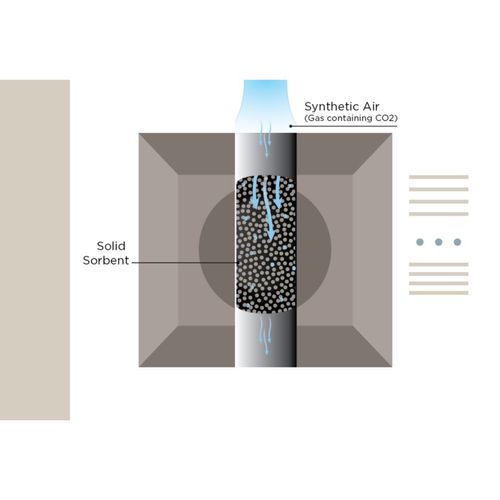

In a new carbon capture testing apparatus, synthetic air flows through a column. The sorbent traps and captures the carbon molecules. The device measures how fast the sorbent becomes saturated with CO₂. // SOURCE: N. Hanacek/NIST

May 1, 2024

BY National Institute of Standards and Technology

Advertisement

Advertisement

Related Stories

Rice University researchers have developed an electrochemical reactor that has the potential to drastically reduce energy consumption for direct air capture (DAC), the removal of carbon dioxide directly from the atmosphere.

Utah State University’s Bingham Research Center has received a grant from the U.S. Department of Energy for a $480,000 project. The grant is part of a larger project called the Uinta-Piceance Basin Carbon Management and Community Engagement Partnership, which is led by the University of Utah.

British Steel is focused on transforming the manufacture of steel into a clean, green and sustainable business by embracing electric arc furnace technology. To support this, and the development of the required technology, a mobile carbon capture pilot plant has been installed at British Steel’s Central Power Station in Scunthorpe.

A new type of absorbing material developed by chemists at the University of California, Berkeley, could help get the world to negative emissions. The porous material — a covalent organic framework — captures CO2 from ambient air without degradation by water or other contaminants, one of the limitations of existing direct air capture (DAC) technologies.

Outside the National Renewable Energy Laboratory’s (NREL's) Research Support Facility and its Café, there are two curious brick pavers unlike the others nearby. These pavers signify the quest of lead researcher Paul Meyer and team, including Julia Sullivan, Kyle Foster, Bob Allen, Jingying Hu, and Heather Goetsch, to unearth a carbon-negative alternative to traditional concrete.